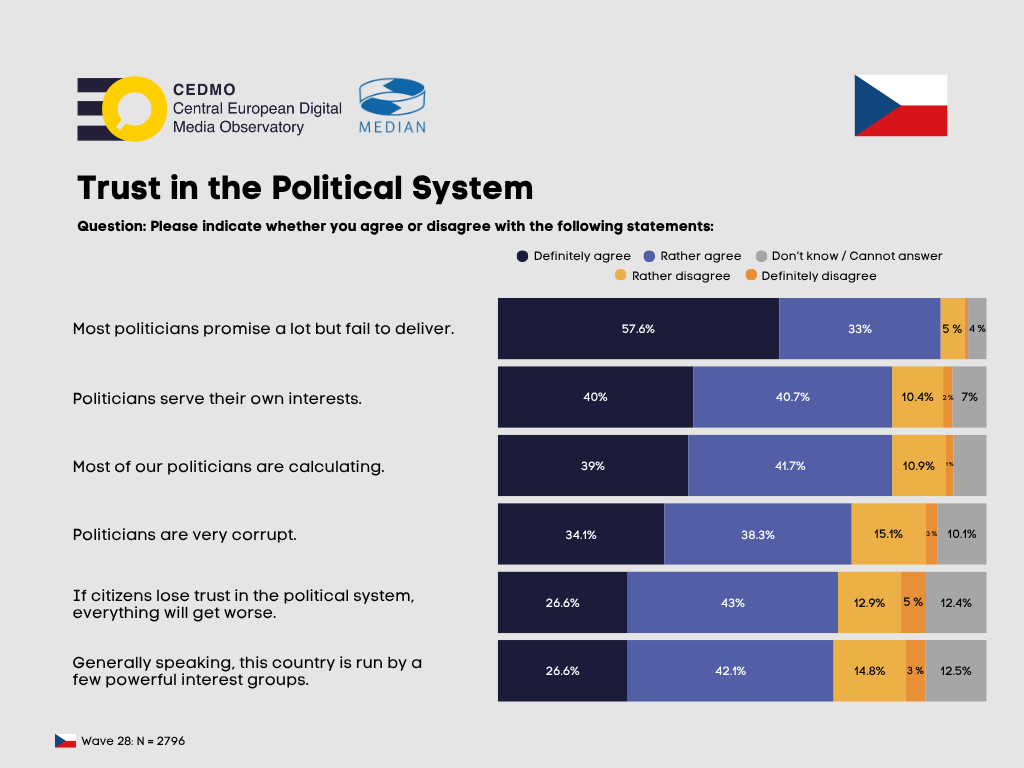

Despite the high level of distrust in politics and the political system, nearly 69% of eligible voters participated in the October elections to the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic. The results of a representative survey by the Central European Digital Media Observatory (CEDMO) show that 91% of respondents do not believe that politicians keep their promises, more than 80% consider them to be calculating and pursuing their own interests, and 72% consider them to be very corrupt. This skepticism may be one of the factors that increase society’s vulnerability to disinformation and influence operations. At the same time, the question arises as to whether these phenomena contribute to its further deepening.

“The pre-election period and the elections themselves provided an opportunity to reflect on public trust in the political system. The results of a representative survey we conducted shortly before the parliamentary elections show that public trust in politicians has been significantly weakened,” says Ivan Ruta Cuker, data analyst and sociologist at CEDMO, adding: “Nine out of ten Czechs do not believe that politicians keep their promises, more than 80% are convinced that they primarily pursue their own interests, and 72% consider them to be very corrupt. Such a degree of skepticism is a warning sign for democratic institutions and politicians themselves.”

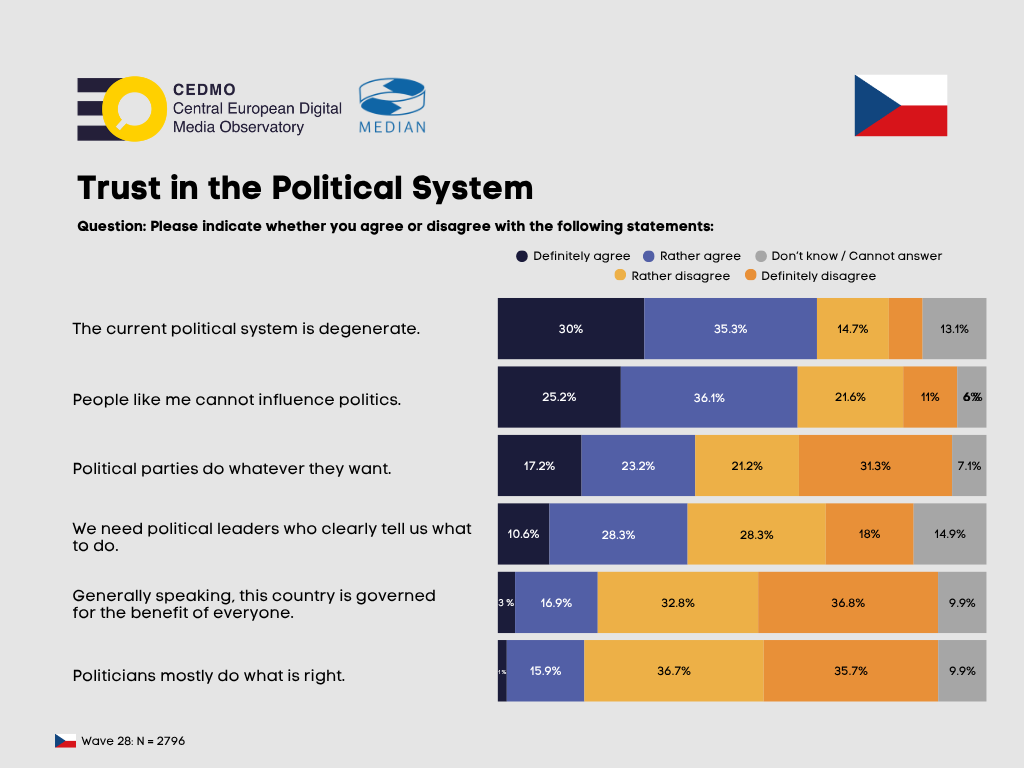

The lowest level of agreement was recorded for the statement “Politicians do the right thing in most cases” – only 17% of respondents agreed with it, while 73% disagreed. A similarly skeptical attitude was evident in the statement “Generally speaking, this country is run for the benefit of all,” with which only 20% of respondents agreed, while 70% disagreed.

The high level of skepticism toward political actors and institutions is also reflected in the willingness of some members of the public to give credence to false or misleading statements. Therefore, as part of the representative CEDMO Trends survey, researchers from Charles University have been monitoring not only the development of public attitudes over the long term, but also specific false reports that appear in the Czech information space. They regularly test several selected reports to determine their reach and how they are perceived by the public in terms of credibility. One such report, whose key message appeared in the digital environment in several different variants in the period before the October parliamentary elections, concerned the newly introduced institution of postal voting.

Postal voting: millions versus thousands of voters

Among the false narratives tested by CEDMO in its September wave of surveys was one claiming that postal voting would allow more than a million compatriots living in the United States and another million around the world to vote in the elections to the Chamber of Deputies. The survey was conducted after the publication of official data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, according to which only 10,905 voters had requested the necessary documents for postal voting. This official information on the actual number of voters also appeared in several Czech mainstream media outlets. Nevertheless, even after this, the false narrative was still considered credible by almost half of the Czech population (46%). CEDMO addressed narratives related to postal voting in more detail in a separate report published before the elections[1] . This false claim is just one example of a whole series of messages aimed at questioning the legitimacy of the elections – often through the suggestive idea that the vote will be manipulated by the government, foreign actors, or other influential groups.

The phenomenon of stolen elections

A similar claim that appeared in the Czech digital information space before the elections was, for example, that President Petr Pavel was considering canceling the upcoming October elections to the Chamber of Deputies and allowing Prime Minister Petr Fiala to continue governing, or that the Security Information Service, in cooperation with the Constitutional Court, was planning to invalidate the October parliamentary elections due to alleged interference by foreign powers, primarily Russia. The second report appeared in the information space even before Deník N published its findings on Sunday, September 28, related to the discovery of hundreds of TikTok accounts attempting to influence the elections, and then its dissemination in various variations intensified. The discovery of fake accounts on TikTok was presented in alternative media as an alleged expected pretext for canceling the elections, linked to the Romanian scenario, the introduction of censorship by European institutions, and the silencing of the opposition to the current government (I, II, III, IV, V, VI).

The narrative of “stolen elections” has repeatedly appeared in Europe since the 2020 US presidential election, when it went viral in connection with a widespread wave of disinformation. Since then, it has been observed in a number of other countries – notably in the 2022 presidential elections in Brazil, in Romania in 2025 (I, II), but also in Moldova (I, II), France (I, II), Germany (I, II), Poland (I, II, III, IV, V), Slovakia, and during the 2024 European Parliament elections (I, II). This type of disinformation usually spreads most intensively after the end of voting, with the election result being a key factor – if the candidate or party that was the main disseminator of disinformation wins, the narrative of rigged elections appears only marginally.

Tommaso Canetta, coordinator of fact-checking activities at the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), deputy director of the Italian projects Pagella Politica and Facta News, and member of the EFCSN’s governing bodies, comments on this phenomenon: “Disinformation about ‘rigged elections’ has become a well-spread phenomenon in Europe since the US elections in 2020. It can have different levels of intensity, that change according to many factors: if the losing faction (considering both the political level and the follower base) is in general a very active spreader of disinformation or not, and if it has a tendency to believe and spread conspiracy theories or not; if foreign powers have an interest in de-legitimizing the winners, spread social unrest, amplify polarization etc. or not; if the country (considering the media/social-media landscape, the political landscape, media literacy levels of the population, trust in institutions, recent history etc.) is more or less susceptible to disinformation. This narrative can be extremely dangerous, because it can lead – like we’ve seen in the past in other non-European countries – to attempted coups and violence in the streets. And even if it doesn’t, it can have repercussions in the following years, increasing societal polarization and eroding trust in democracy and institutions.“

Disinformation narratives recorded by fact-checkers before the elections

Other disinformation narratives that emerged in connection with the October elections to the Chamber of Deputies include the topic of so-called hidden coalitions and the spread of deepfake hoaxes exploiting the faces of politicians. The issue of hidden coalitions became one of the central points of the pre-election campaign, especially after the regional courts’ decisions concerning the Stačilo! and SPD movements. In the period between these decisions and the subsequent ruling of the Constitutional Court, which confirmed that both movements could run independently, a number of misleading claims appeared in the public sphere. Demagog.cz, for example, drew attention to a post by MEP Kateřina Konečná, who interpreted the regional courts’ decisions as confirmation that Stačilo! is not an unacknowledged coalition – even though the courts described the long-standing practice of hidden coalitions as circumventing the law.

The second prominent narrative was fraudulent investment advertisements using deepfake videos featuring the faces of Czech politicians. Before the elections, fake recordings appeared on social media featuring Interior Minister Vít Rakušan, ANO movement vice-chair Alena Schillerová, and SPD chairman Tomio Okamura. The aim of these videos was to lure users to non-existent investment platforms and obtain sensitive data or money from them. Fraudsters in the campaign more often used politicians across the political spectrum. In addition to the aforementioned personalities, Prime Minister Petr Fiala, President Petr Pavel, Finance Minister Zbyněk Stanjura, and ANO movement chairman Andrej Babiš had also appeared in these videos earlier. In addition to a series of fraudulent deepfake videos misusing the likenesses of Czech politicians, Demagog.cz also recorded a post explicitly calling for the killing of a member of the government.

The third significant narrative was manipulation targeting Ukrainians living in Czechia. Claims appeared in the public sphere about their alleged advantages over Czech citizens and increased crime. For example, SPD leader Tomio Okamura claimed on Facebook that Interior Minister Vít Rakušan had insulted Czechs by saying that Ukrainians behave better. In reality, however, Rakušan was only talking about crime, and according to data from the Czech Police, Ukrainians commit fewer crimes per capita. Okamura omitted this context and presented the statement in a sponsored video as a general assessment of the behavior of Czechs and Ukrainians. Another SPD candidate, Jiří Fořt, then spread false information in a video with more than 650,000 views about the school attendance of Ukrainian children and alleged financial rewards for their families.

The fourth narrative was disinformation about alleged statements by President Petr Pavel. A post spread on social media claiming that during a meeting in Pardubice, the president had said that older people should no longer have the right to vote, that he wanted to grant citizenship to all Ukrainian refugees, and that he wanted to ban certain political parties. However, the recording of the debate contains nothing of the sort, and there is no evidence that the president ever made such proposals. His spokesperson dismissed these claims as deliberately spread falsehoods and pointed out that the president does not have the power to restrict the right to vote.

*The report publishes data from a wave of measurements that took place in July and August. The survey within the currently published wave of the CEDMO Trends longitudinal survey took place in September 2025.

The thematic report is available in the following versions:

- CEDMO Special Brief (data for Czechia and Slovakia) – in Czech

- CEDMO Special Brief (data for Czechia and Slovakia) – in English

CEDMO will continue to monitor developments in public opinion and the information environment in connection with the parliamentary elections. Further findings will be available on the observatory’s website: cedmohub.eu

*CEDMO Trends offers exceptional insight into the development of population behavior in the consumption of various types of media content, focusing on individual types of information disorders such as misinformation and disinformation. These not only weaken public trust in the institutions necessary for the functioning of a pluralistic democracy, but can also amplify individual infodemics. For CEDMO (Central European Digital Media Observatory), it is conducted in the Czech Republic by the Median research agency on a representative sample of 2,700–3,000 respondents over the age of 16.

*The CEDMO TRENDS research in the Czech Republic is funded by the National Recovery Plan as part of project 1.4 CEDMO 1 – Z220312000000 Support for increasing the impact, innovation, and sustainability of CEDMO in the Czech Republic.

*The publication of the CEDMO Special Brief “Disinformation narratives in the context of the elections to the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic in October 2025” was financially supported by the National Recovery Plan, the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility program, as part of project 1.4 CEDMO 1 – Z220312000000, Support for increasing the impact, innovation, and sustainability of CEDMO in the Czech Republic.