On Sunday, June 1, 2025, the second round of presidential elections took place in Poland, in which Karol Nawrocki (51%) narrowly defeated Rafał Trzaskowski (49%). Immediately after the polls closed, we surveyed Polish citizens to gauge their concerns about efforts by foreign powers and supranational institutions to influence the election results. At the same time, we monitored information manipulation spreading in the digital space during the campaign. In view of the upcoming elections to the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic, which will take place in October 2025, the CEDMO research team also conducted a comparison with the Czech Republic and Slovakia, where the next parliamentary elections are scheduled to take place in the fall of 2027. We provide a clear summary of the findings in CEDMO Special Brief – Poland‘s 2025 presidential election: electoral interference and politicalorientation in Central Europe.

Czech men and women participating in the representative long-term CEDMO Trends survey in June 2025 stated that, in connection with the upcoming autumn parliamentary elections, they consider efforts to influence the results of the vote by Russia (42%), the European Union (41%), and the United States (29%) to be likely.

Respondents in Poland, surveyed a few days after the second round of the presidential elections, expressed essentially similar views to those in the Czech Republic. They considered Russia (47%) to be the most likely to influence the elections, followed by the European Union (39%) and the United States (35%).

In contrast, the attitudes of Slovak respondents differ quite significantly from those of Czechs and Poles. Slovaks perceive the European Union (46%) as the most likely actor to interfere in the elections, followed by the United States (39%) and, in third place, Russia (38%).

Compared to an earlier survey conducted by CEDMO before the European Parliament elections in spring 2024, the current results are similar, especially in the case of Czech respondents. The most significant change is a decline in concerns about Russian influence on the elections in Poland (from 63% to 42%). In Slovakia, there was a slight increase in the proportion of respondents who consider EU influence on the elections likely.

Young Czechs are the most politically polarized

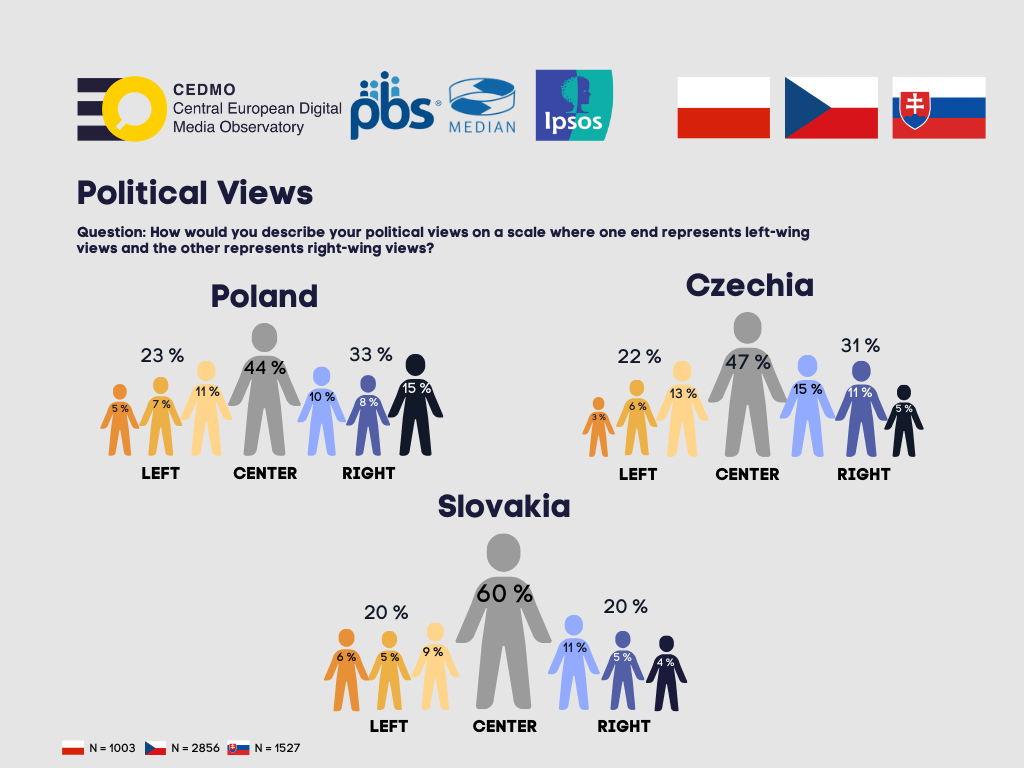

On the political spectrum—from left-wing to right-wing views—respondents in all three countries most often identify themselves as centrist voters. “While a centrist political orientation prevails across all three countries — the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia — the youngest respondents aged 16 to 24 in the Czech Republic hold significantly more polarized views,” says sociologist and CEDMO data analyst Ivan Ruta Cuker, adding:

“This age group is more likely than others to lean either to the left or to the right, with centrist views less prevalent among them. More than a quarter of young Czechs identify as left-wing, and more than a third as right-wing. In contrast, young Slovaks and Poles, for example, have a higher proportion of centrists. It is also interesting to note that in the Czech Republic, the largest proportion of centrist voters is among young adults aged 25 to 34.”

Migration, climate, and questioning the integrity of elections

Fact-checking organizations involved in the CEDMO hub (Demagog.pl, Demagog.cz, Demagog.sk, and AFP) recorded the spread of a wide range of disinformation narratives during the Polish presidential campaign. These most often concerned migration, climate policy, and the integrity of elections.

In the area of migration, claims about so-called “apartments for illegal migrants” allegedly set up in integration centers dominated, even though these facilities do not provide any accommodation. There were also inaccurate interpretations of statistics on the movement of people at the borders and false claims that Ukrainian refugees were a burden on the state budget, even though the data shows the opposite.

Some disinformation directly questioned the legitimacy of the elections, for example by claiming that migrants could vote, that ballot papers would be manipulated using erasable pens, or that one voter could vote multiple times. These narratives can undermine public trust in democratic processes.

False statements about EU climate policy also appeared in the campaign. Candidates questioned the existence of the Green Deal or provided misleading information about its costs. One candidate even claimed that achieving zero CO₂ emissions would make it impossible to breathe.

Fraud and AI-generated content

A number of fraudulent posts appeared online, misusing the image of presidential candidates or people associated with them. Some of them were created using artificial intelligence, while others were based on modified or cropped images. The aim was either to ridicule politicians or to obtain personal data and money from users.

Deepfakes and posts that, according to available evidence, could have been part of Russian disinformation campaigns were also recorded. However, politicians themselves also used artificial intelligence, for example to create promotional visuals with fictitious supporters.

AI was also used to circumvent the election moratorium – visuals of candidates were spread on social media to symbolically suggest who to vote for. These posts were also often generated by artificial intelligence.

A complete overview of the research results and analysis of disinformation narratives is available in a special edition of CEDMO Special Brief, which is freely available at www.cedmohub.eu.

The thematic report is available in the following versions:

- CEDMO Special Brief (data from Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia) – in Czech

- CEDMO Special Brief (data from Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia) – in Polish

- CEDMO Special Brief (data from Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia) – in Slovak

- CEDMO Special Brief (data from Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia) – in English

*CEDMO Trends offers unique insight into how people are changing their media consumption habits, focusing on specific types of information problems like misinformation and disinformation. These not only weaken public trust in institutions that are essential for a functioning democracy, but can also amplify individual infodemics. For CEDMO (Central European Digital Media Observatory), it is conducted in the Czech Republic by the research agency Median on a representative sample of 2,700–3,000 respondents aged 16 and older. In Slovakia, it is carried out by the IPSOS research agency on a representative sample of more than 1,600–2,300 respondents aged 16 and older.

*CEDMO TRENDS research in the Czech Republic is funded by the National Recovery Plan under project 1.4 CEDMO 1 – Z220312000000 Support for increasing the impact, innovation, and sustainability of CEDMO in the Czech Republic. Data collection in Slovakia is funded by the National Recovery Plan — project MPO 60273/24/21300/21000 CEDMO 2.0 NPO.

*CEDMO Special Brief Presidential Elections in Poland 2025: Election Interference and Political Orientation in Central Europe was produced as part of project 101158609 co-financed by the European Union under call DIGITAL-2023-DEPLOY-04. The content of the publication and press releases reflects only the views of the independent CEDMO consortium, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

*This publication is part of an international project funded by the European Union (action number 101158609) and co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education under the Minister of Science and Higher Education program entitled “PMW” for the period 2024-2026 (contract number 6054/DIGITAL/2024/2025/2). However, the views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. Neither the European Union nor the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education are responsible for them.