Research conducted as part of CEDMO 2.0

In the first phase of research conducted as part of the Central European Digital Media Observatory, SWPS University, in cooperation with partners from the Czech Republic and Slovakia, carried out three comparative studies concerning Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia.

The research was conducted by a team consisting of: Karina Stasiuk-Krajewska (leader), Michał Wenzel, Jakub Kuś, and Ivan R. Cuker.

STUDY 1

The first study, “Disinformation narratives in fake news in Polish / Czech / Slovak and their semantic structure,” concerned narratives and semantic structures in fake news media messages. The study was conducted on a sample of 1,563 pieces of fake news (1,020 from Poland, 263 from the Czech Republic, and 280 from Slovakia) published between January 2023 and November 2024.

The analysis covered messages that were considered fake news by fact-checking organizations collaborating within the CEDMO 2.0 project (AFP and Demagog in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia). In particular, the analysis included news items marked as fake news that referred to facts (provided false or manipulated information/data). Therefore, debunks referring to statements made by politicians were not analyzed.

The methodology used is intermediate between the classic qualitative method (case study) and the quantitative method. Thanks to this, by analyzing several hundred examples according to previously adopted categories (tested in earlier CEDMO studies and modified on the basis of experience gained during the implementation of this study), it is possible to capture the dominant trends in the structure of fake news messages. In turn, the use of elements of qualitative analysis allows us to answer the question about the interrelationships between individual elements and their functions in the analyzed messages in relation to the audience.

In the context of the study, questions were asked about:

The format of the message (text, image, sound), as well as what stories fake news messages tell – what characters (actors) appear in them and in what roles, what is the space in which the events take place; what the conflict is about (i.e., the problem to which the fake news messages refer); when the story is told and whether the presence of the narrator (author) is clearly visible in the text.

According to the accepted assumptions, identifying the dominant features of fake news messages will make it easier to recognize them and more precisely define the reception skills that are important in this context.

What are the main conclusions of the study, and what is their practical significance?

The structure of fake news

Fake news can be considered a collection of texts that are relatively consistent in terms of structure (genre), as confirmed by previous research and analyses conducted by the CEDMO consortium. Fake news imitates journalistic information and thus gains credibility. However, its subject matter is diverse and directly related not only to the current socio-political situation, but also to the main areas of interest of the professional media. Fake news, unlike fairy tales, for example, refers to current events. Therefore, it cannot be fully consistent in terms of narrative.

- Practical significance

Although fake news is a relatively consistent genre, its subject matter (like that of other disinformation activities) changes dynamically depending on the context. The narratives that dominate fake news are therefore subject to modification, which is why particular attention should be paid to the selection of current examples and topics for analysis.

The form of disinformation messages, such as fake news

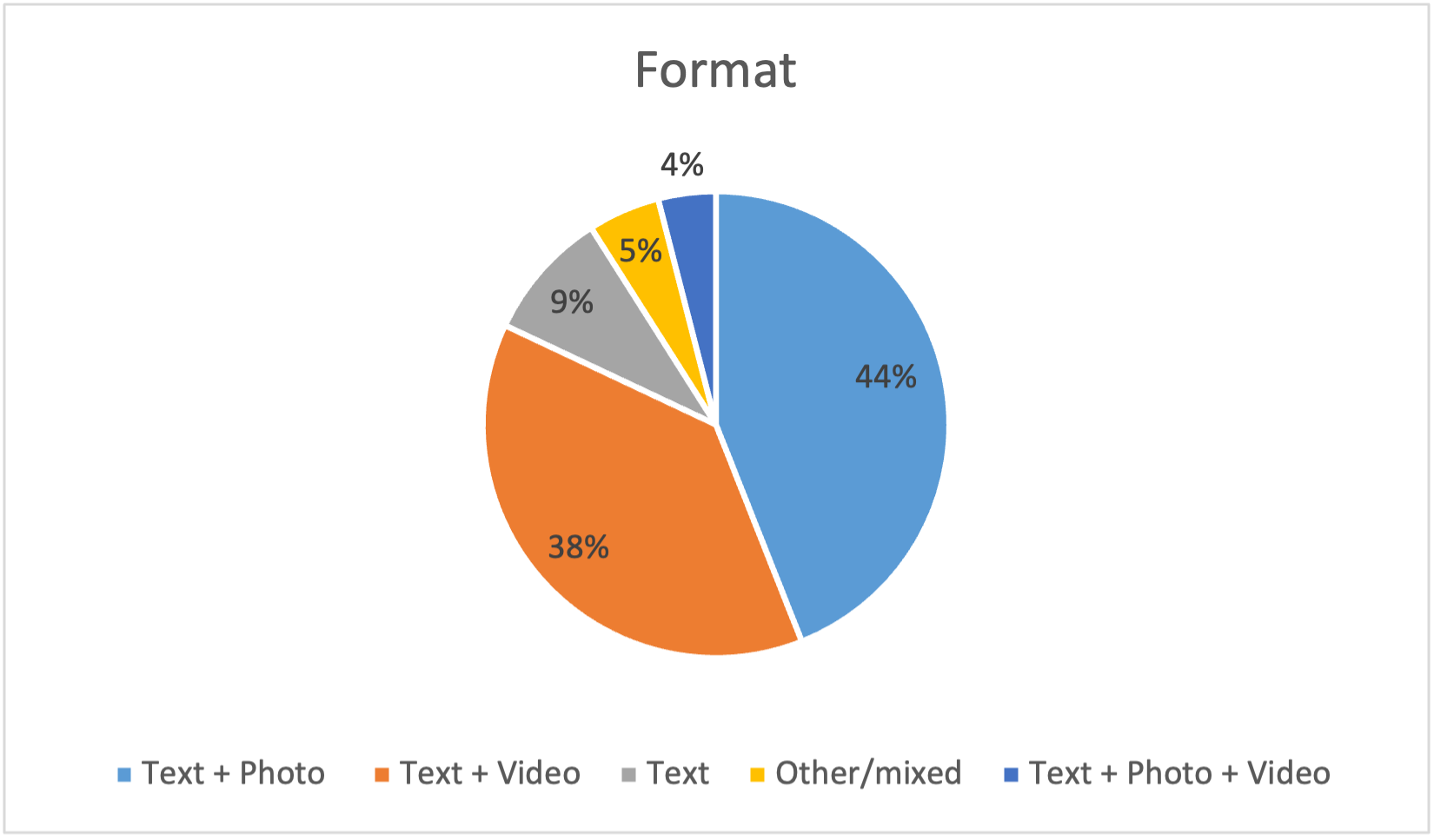

In terms of format, the analyzed messages confirm the importance of visual communication in media messages. The vast majority of fake news uses images – both static (44%) and dynamic (38%). Interestingly, however, images are not a standalone code – in almost every case, they are accompanied by text, the format and function of which vary. Only 9% of the messages analyzed consist of only one type of code – in this case, text. In this sense, fake news messages are multimodal – they consist of different types of codes.

- Practical significance

Fake news messages are multimodal and therefore consist of different types of codes (e.g., image, sound, text). It is therefore necessary to build the audience’s resistance to all codes present in this type of message – not only by teaching them to understand written text, but also to critically decode images. It is also important to provide information about tools that allow for the verification of all types of codes.

The main actors in fake news

The types of characters in the analyzed messages are quite diverse. Institutional actors (e.g., governments or international organizations) and politicians (understood as individuals) account for 19% each. In 18% of the messages, the main characters are so-called “ordinary people”, and in 16%, specialists (doctors, professors, etc). The roles assigned to particular types of actors are characteristic – institutions and politicians are most often presented in a negative light, as a source of oppression, while ordinary people are usually victims of this oppression, victims of actions taken by politicians or institutions in power. The exception is the category of refugees – in this case, “ordinary people” are portrayed as a source of danger. This character profile points to a specific construction of the social world that appears in fake news – it is a hostile world, seen through the prism of the daily injustices experienced by “ordinary people” at the hands of politicians or institutions in power, or possibly representatives of culturally different groups (most often refugees).

- Practical significance

Disinformation conveys a specific vision of the world in which the main characters are ordinary people who fall victim to influential individuals or institutions. This feature should be taken into account when selecting examples, and it should also be remembered that the discussion may lead to reflections on equality and power in democratic societies. It can also be assumed that participants will identify with the victims (according to the narrative of fake news), who are ordinary people.

Context

The narrative of fake news is clearly set in the public rather than the private sphere, in the city rather than outside it (only 10% of the messages analyzed are set in the private sphere and outside the city). The world presented in fake news is therefore a world of public experiences, social and civic issues, and, to a lesser extent, private ones. It is also a world of the center, not the periphery. Things that happen in the center and are public in nature will therefore most often be the subject of manipulation in this type of message.

- Practical significance

Typical disinformation is more central than peripheral in nature and concerns public rather than private life. It can be assumed that this dominance reflects the belief that these aspects are more socially important. This belief may also be shared by the target audience of educational activities.

Problem (conflict)

Despite numerous similarities in terms of the analyzed narrative elements, fake news in the three countries (languages) analyzed has its own thematic specificity. Overall, fake news about the war in Ukraine dominated the analyzed time period, but medical disinformation clearly gained in importance (especially in Poland). Politicians were also the subject of fake news (often their private lives or alleged abuses they had committed).

- Practical significance

When conducting educational activities, it is important to remember that although disinformation is a global phenomenon, there are significant differences between countries in terms of narrative. In this context, particular attention should be paid to the selection of examples and the trainer’s good understanding of local conditions – not only at the national level, but also at the regional level, and even the specific characteristics of the target group.

Presence of the author in the text

A characteristic feature of fake news messages is the presence of the author (narrator) in the text. This applies to 70% of the cases analyzed. The author reveals themselves directly (for example, through grammatical forms – first-person singular verbs), but also indirectly – through direct references to the addressee, declarations, or rhetorical questions.

- Practical significance

Here, it is clear that fake news is highly persuasive – the presence of the author directly suggests a specific interpretation of the message. This is also a clear difference from classic journalistic information, where the author of the text is not and should not be present. In this context, it should be emphasized that objectivity understood in this way is particularly important for professional journalism because, from the reader’s point of view, it is one of the most important clues for distinguishing between journalistic messages and fake news.

STUDY 2

The second study, “Rhetoric of fake news in Poland / Czechia / Slovakia (content analysis),“ concerned the means of persuasion (convincing) and legitimization (credibility) in fake news media messages. The study was conducted on a sample of 1,523 fake news items (1,020 from Poland, 263 from the Czech Republic, and 280 from Slovakia) published between January 2023 and November 2024.

The analysis covered messages that were considered fake news by fact-checking organizations collaborating within the CEDMO 2.0 project (AFP and Demagog in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia). In particular, the analysis included news items marked as fake news that referred to facts (provided false or manipulated information/data). Therefore, debunks referring to statements made by politicians were not analyzed.

The methodology used is intermediate between the classic qualitative method (case study) and the quantitative method. Thanks to this, by analyzing several hundred examples according to previously adopted categories (tested in earlier CEDMO studies and modified on the basis of experience gained during the implementation of this study), it is possible to capture the dominant trends in the structure of fake news messages. In turn, the use of elements of qualitative analysis allows us to answer the question about the interrelationships between individual elements and their functions in the analyzed messages in relation to the audience.

In accordance with the adopted assumptions, identifying the dominant features of fake news messages will make it easier to recognize them and more precisely define the reception skills that are important in this context.

What are the main conclusions of the research, and what is their practical significance?

Framing (context)

Fake news clearly refers to conspiracy theories. In 37% of messages, the main frame (context) for presenting the message is a conspiracy theory. Next in importance is the depreciation of authority (27%) and conflict and violence among elites (12% each). Fake news is shaped by conflict and polarization. There is a clearly visible vision of the modern world based on conflict and violence—especially violence by those in power against those who are not. This violence is therefore perceived as unjust and based on concealing the truth about the world.

- Practical significance

Special attention should be paid to conspiracy theories, as they are inextricably linked to fake news, and their mechanisms are similar and partly identical to those of disinformation. In other words, there is no disinformation without conspiracy theories and no conspiracy theories without disinformation. Examples corresponding to the assumptions of conspiracy theories should be selected, and educational activities should be conducted in such a way as to reveal the mechanisms and build resistance to both phenomena simultaneously.

It is important to remember that disinformation narratives are closely linked to a specific way of interpreting the world (discourse) based on the assumption that the world is polarized and violent. Therefore, one should be prepared for this type of argumentation and be careful not to confirm this view of the world. Typical examples of fake news should be selected, i.e., those based on a framework of violence and polarization.

Main rhetorical devices

The rhetoric of fake news refers to emotions and/or areas that evoke emotions (in connection with polarization), and on the other hand, it correlates with the characteristic features of conspiracy theories, such as linking distant facts or misusing concepts (and thus creating specific semantics and, consequently, alternative interpretations of the world).

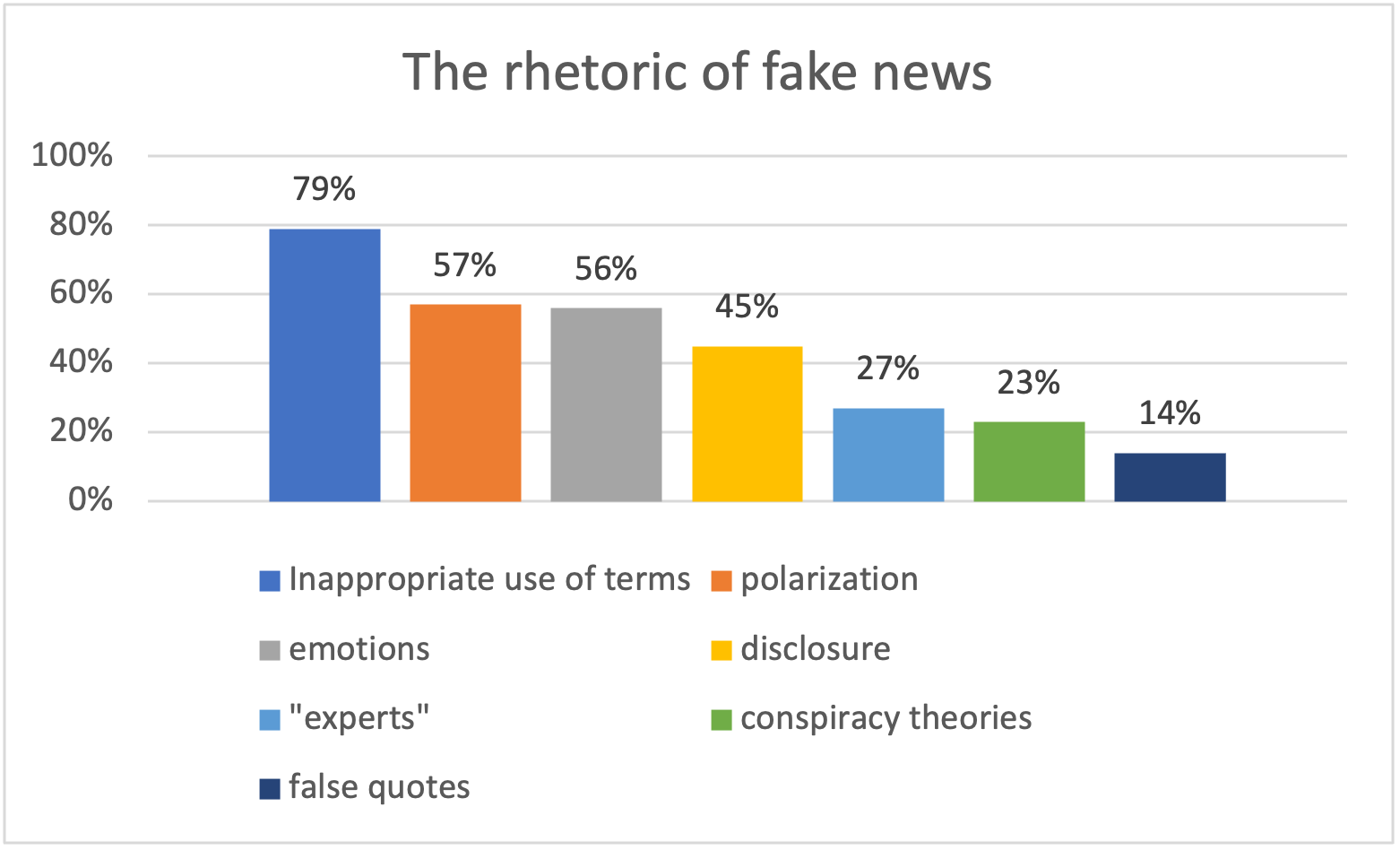

In terms of specific tools of persuasion, the abuse of emotional or labeling terms (such as betrayal, fraud, invader, etc.) clearly dominates, occurring in 79% of messages. This is followed by polarization and emotions (57% and 56%, respectively) and the disclosure of what is hidden (45%). In 41% of cases, fake news uses the rhetorical function of referring to (“alternative”) authorities or manipulating quotes from people considered to be authorities. In this respect, they are similar to hard news.

- Practical significance

In educational activities, particular attention should be paid to developing a critical approach to the emotions contained in media messages and to the seemingly logical reasoning (conclusions) that are characteristic of conspiracy theories. In this context, it is necessary to promote the use of slow thinking rather than fast thinking when dealing with the media.

Care should also be taken to define concepts precisely and to pay particular attention to situations in which these concepts are used in a manipulative way. It should also be remembered that fake news imitates journalistic information. Therefore, attention should be paid to the skills involved in distinguishing between these two types of messages (e.g., by checking sources), but care should also be taken to ensure that efforts to build resilience to fake news are not seen as undermining trust in reliable sources of information.

Means of legitimization (building credibility)

The legitimization of fake news is mainly based on references to ethical norms, and thus to the “proper” world order and moral principles. For example, it is argued that a given action is wrong, immoral, harmful, violates fundamental human rights, etc. Such arguments appear in 52% of the messages analyzed. This is followed by rationalization (52%), i.e., lending credibility by providing data or rational arguments.

Thirty-four percent of the messages analyzed are legitimized by referring to authorities (most often “alternative” ones), while 22% are legitimized by distancing themselves from and taking an ironic approach to their surroundings. As can be seen, the reality constructed by fake news is, to some extent, a reality of data and authority, but above all, it is a world of moral judgments directed against actions that disrupt the proper (natural, just) order of things.

- Practical significance

Fake news builds its credibility primarily by appealing to moral values, to the categories of good and evil. This poses a serious challenge in the context of educational activities, as one must be prepared for in-depth ideological and moral discussions about the world order. Caution should also be exercised when assessing the specific beliefs of participants, as these may be an important element of their moral assessment of reality. It is also worth remembering that there is a significant group of “alternative” authorities, whose citations are equated with obvious credibility.

STUDY 3

Study 3 was titled: “Structure of disinformation: Content attributes and susceptibility to disinformation in Poland, Czechia and Slovakia.” One of the key areas in the field of disinformation research is determining the structure of these messages that makes them convincing to recipients. As part of the experimental study, we determined which attributes contribute to increasing the “impact” of messages aimed at manipulating and confusing recipients. We were particularly interested in factors such as: the emotionality of the message, the presence of a visible author (subjectively perceived possibility of attributing authorship), as well as the argumentation or justification of the message – references to (pseudo)science or ethical reasons. In the study, we used an experimental design on samples representative of the populations of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia.

Research objectives

In the study, we tested hypotheses concerning the influence of factors related to the content of disinformation messages. As part of establishing the experimental procedure, we identified fixed and variable factors.

The fixed factors were: elements of conspiracy theory (containing references to social conflicts) and the structure of the material – the combination of text and graphics.

Variable factors were the subject of the experiment. They concerned: 1. the emotionality of the message; 2. the marked role of the author, i.e., the clearly indicated authorship of the message; 3. rationalization, i.e., justification referring to science or moral testimony (reference to values).

Procedure

The study consisted of two experiments in a “2×2” scheme. We used two sets of authentic disinformation materials, identified as such by Demagog, a leading fact-checking organization. The original material was modified to reflect the research hypotheses regarding the structure of this type of message. Each respondent randomly received one image from the first set (X1, X1a, X1b, X1c) and one from the second set (X2, X2a, X2b, X2c). As a result, each respondent received two images for evaluation (randomly selected from groups 1 and 2) and answered questions about both images. The selection of images from both groups was independent of each other. The assignment of respondents to groups was random. Respondents answered a series of similar questions concerning 11 dimensions of disinformation.

The survey was conducted by PBS on between the 14th and 18th of April 14-18, 2025, in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. The interviews were conducted using the CAWI method.

Results

Overall susceptibility to disinformation

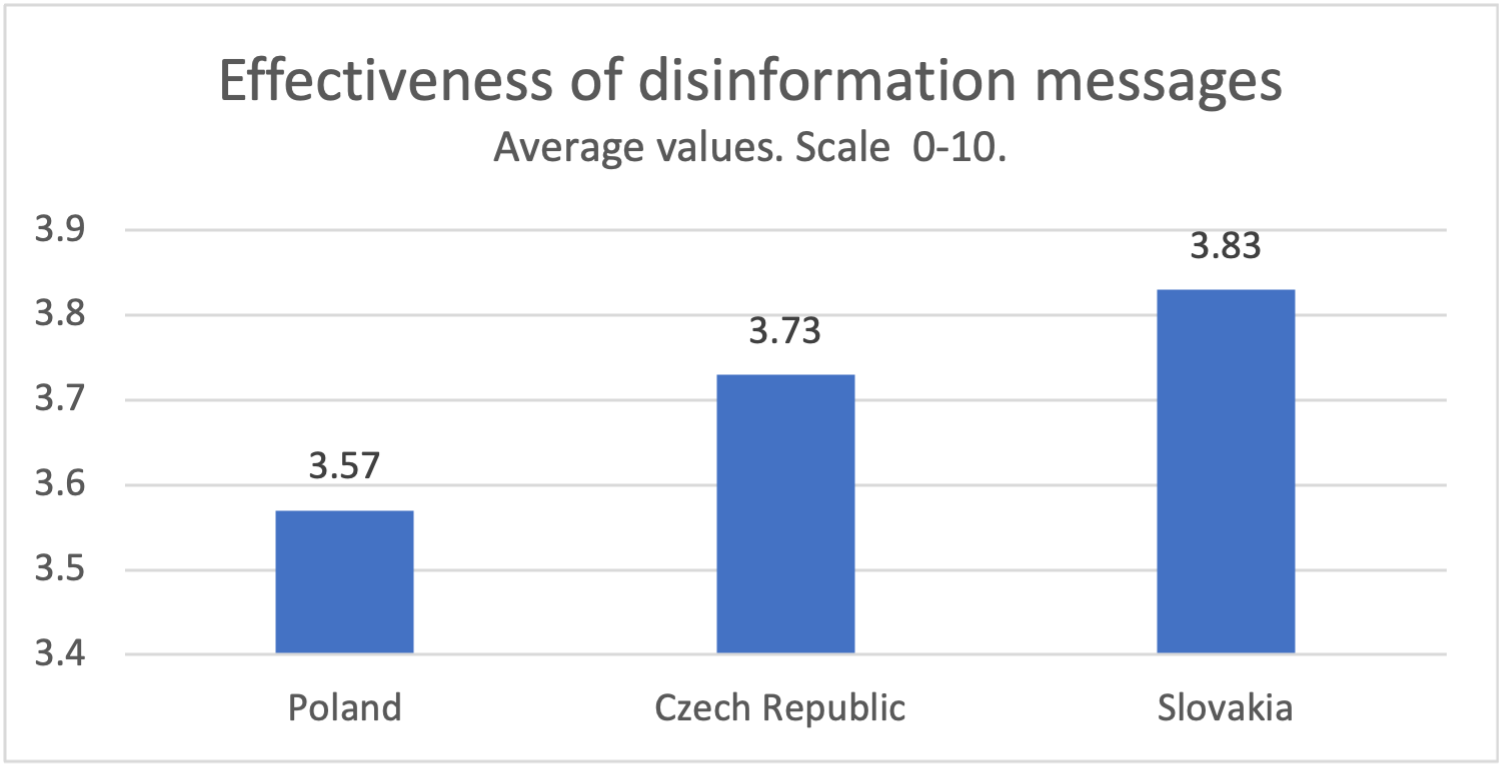

The first conclusion from the study: society is largely resistant to disinformation. The content shown is correctly recognized as attempts to mislead. In the case of disinformation materials, the prevailing opinion is that they are: an attempt at manipulation, an expression of the interests of a social or professional group, and that they are based on rumors, beliefs, or myths. At the same time, they are not perceived as true, fact-based, verifiable at source, prepared reliably, or prepared with good intentions; they do not affect respondents personally or encourage them to take action. This result applies to all three societies surveyed. Vulnerability is greater in the Czech Republic and Slovakia than in Poland.

Emotionality of the message

Our main research questions concerned the characteristics of the messages and their impact on the evaluation of the presented material. The emotionality of the message (dramatic photo) combined with the lack of an identifiable author made the message significantly less credible: it was clearly less often considered true, reliable, fact-based, and prepared with good intentions, and was more strongly perceived as an attempt at manipulation. This was the case in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia.

Media consumers, therefore, recognize the manipulative intent behind the combination of content with a photo that is visible from a distance (large red letters) and disturbing (faces resembling enslaved people). In manipulative messages, such graphics serve to attract attention. However, it turns out that this comes at the expense of the message’s effectiveness. The dramatic photo serves as a warning to recipients about the sender’s intentions.

Rationalization

Depersonalization and reference to (quasi- or pseudo-)scientific arguments increase the effectiveness of the message. A neutral and impersonal message is clearly the most convincing. It most closely resembles a professional information message.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools

The study also addressed the issue of using artificial intelligence (AI) in the production of materials. Recognizing AI-generated content is a subjective and objective problem for respondents.

This publication is part of an international project funded by the European Union (action no. 101158609) and co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education under the program entitled “Co-financed International Projects” in 2024-2026 (agreement no. 6054/DIGITAL/2024/2025/2).

However, the views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA), or the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. Neither the European Union, the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA), nor the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education are responsible for them.