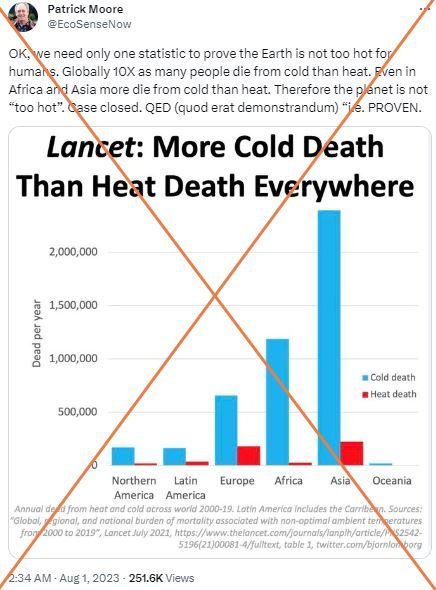

Patrick Moore, former president of Greenpeace Canada, claims statistics showing more deaths attributed to cold temperatures than to heat prove “Earth is not too hot for humans.” This is misleading; experts say gathering such data is complex and that global warming does result in more sickness and fatalities — particularly among vulnerable populations.

“OK, we need only one statistic to prove the Earth is not too hot for humans,” Moore says in an August 1, 2023 post on Twitter, which is being rebranded as “X.”

“Globally 10X as many people die from cold than heat. Even in Africa and Asia more die from cold than heat. Therefore the planet is not ‘too hot’. Case closed.”

Moore has previously promoted misinformation about climate change and his links to Greenpeace. His claim about heat- and cold-related deaths also spread on Facebook.

A reverse image search reveals the chart Moore included in his post has circulated online since at least November 2022. The data comes from a study published in The Lancet in July 2021.

The article (archived here) examines fatalities triggered by “non-optimal” temperatures worldwide. It concludes most excess deaths between 2000 and 2019 were linked to cold rather than hot temperatures.

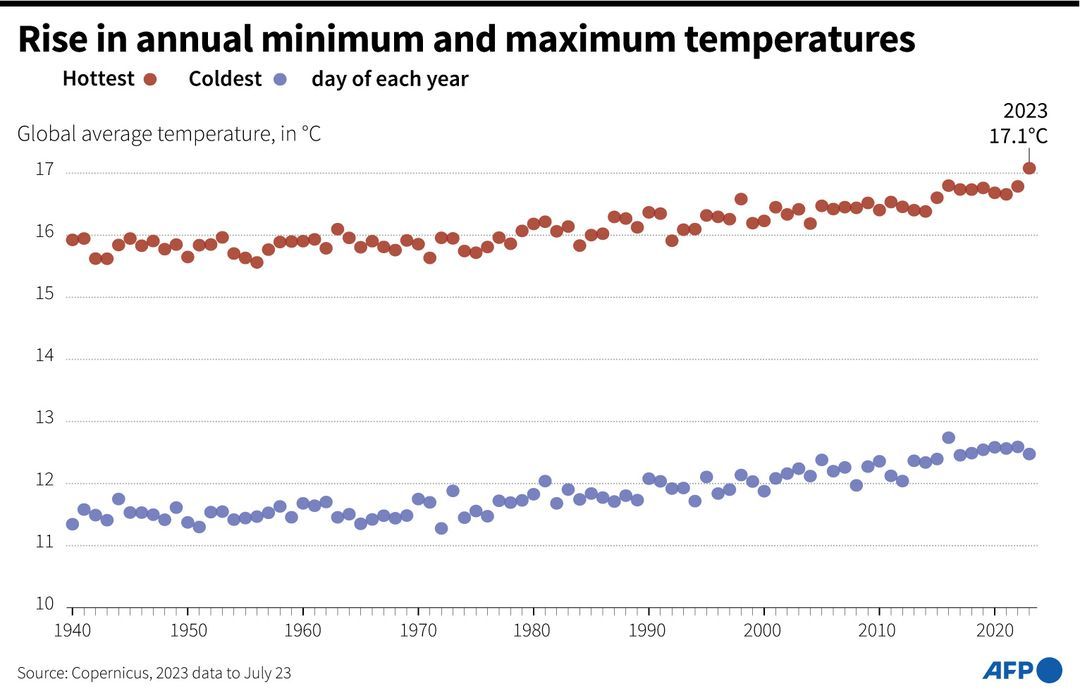

“The global daily mean temperature increased by 0.26 (degrees Celsius) per decade during this time, paralleled with a large decrease in cold-related deaths and a moderate increase in heat-related deaths,” the authors wrote. “The results indicate that global warming might slightly reduce the net temperature-related deaths, although, in the long run, climate change is expected to increase mortality burden.”

Yuming Guo, one of the study’s co-authors, told AFP that Moore’s post misinterprets the data.

“Climate deniers only use daily temperature and mortality as an example to suspect climate change impacts,” he said August 2. “This is not making sense. We should consider the whole picture of the impacts of climate change.”

Guo, who teaches global environmental health and biostatistics at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, said his team found “there will be a net increase in temperature-related deaths in most parts of the world” due to global warming.

Other studies have shown an increase in deaths and diseases linked to heatwave events in the past decade (archived here).

‘Underreported everywhere’

Caradee Wright, chief specialist scientist at South African Medical Research Council, told AFP that getting accurate data on heat-related health issues is complex.

“Heat deaths are grossly underreported everywhere,” she said August 3. “We don’t have good data on mortality and morbidity from many low- and middle-income countries around the world where heat is a problem.”

A heat stroke patient who goes to a hospital or clinic will likely be diagnosed with underlying conditions such as diabetes or breathing difficulties, Wright added, which may ultimately be cited as the cause of death.

She pointed to farm workers who died of heat stroke in different parts of South Africa in January 2023, adding that people working outside in harsh conditions and those who lack fans, water or air conditioning “will bear the brunt of heat-health impacts.”

‘Broader concerns’

Hot weather alone is not the only element to blame for heat-related deaths, experts told AFP.

“The bigger concern is not that heat stress will lead to mortality immediately,” said Nishad Jayasundara, assistant professor of environmental toxicology at Duke Global Health Institute, on August 2.

Instead, he cited “the broader concerns” linked to global warming, such as an increase in infectious disease agents and vector-borne diseases; heat exposure and dehydration gradually deteriorating organs; and health consequences related to a decrease in air and water quality.

“We have to be extremely cautious about simple comparisons of heat-related deaths and cold-related deaths, because of the way our bodies deal with cold stress and heat stress,” Jayasundara said. “One has to look at (the) context in which these mortality events occurred and weigh in comorbidities, age and socio-economic factors.”

Jun Wu, a professor of environmental and occupational health at the University of California-Irvine, agreed. She told AFP on August 3 that hot weather “may also increase compound risk due to other environmental exposures such as air pollution and wildfire smoke.”

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said in its 2021 report (archived here) that each of the past four decades has been warmer than any preceding decade since 1850.

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land,” the panel said.

Depending on future warming levels and location, the proportion of people exposed to deadly heat stress is projected to increase from 30 percent to 48-76 percent by the end of the century, according to IPCC data (archived here).

AFP has investigated other false and misleading claims about climate change here.